Senegal’s Ousmane Sembène Was a True Cinematic Revolutionary

The Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène earned his reputation as the father of African cinema with a series of brilliant movies. Socialist and anti-colonial politics had a profound influence on Sembène, who was also one of Africa’s great novelists.

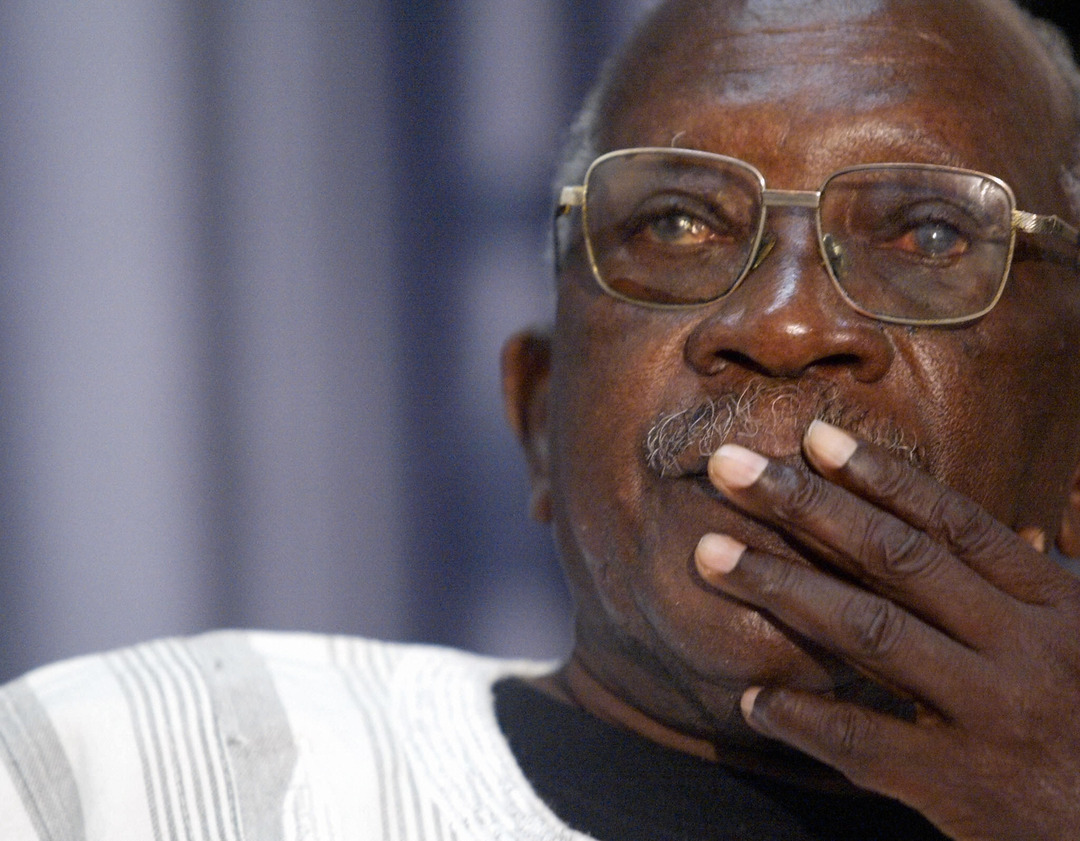

Senegalese writer and director Ousmane Sembène listens during a film class during Dakar’s sixth neighborhood film festival on December 17, 2004. (Sellyou / AFP via Getty Images)

Commentaries on Ousmane Sembène often hail the Senegalese director as the “father of African cinema,” a pioneer with an illustrious string of firsts to his name: the first film shot in Africa by a sub-Saharan African, Borom Sarret (1962); the first feature film, Black Girl (1966); and the first film in a sub-Saharan African language, Mandabi (1968).

These were not the only achievements he had to his name. Sembène also just happened to be one of the continent’s great twentieth-century novelists. Before his artistic career, he had been a fisherman, a mechanic, a soldier, a docker, and a trade union activist.

The vast majority of cultural figures in France’s African empire were products of a colonial education against which they sought to rebel to various degrees, which makes Sembène’s artistic trajectory pretty unique. How did this son of a fisherman without much formal education rise to become one of the giants of twentieth-century African culture?

A Working-Class African Literature

In 1956, Sembène published his first novel, The Black Docker. In part a realist portrait of working-class life in the Marseille docklands, the book followed the well-worn advice that novelists should write from their own experience. However, it also contained a reflection on literary representation and the difficulties faced by Africans in having their stories heard.

The doomed protagonist is an aspiring writer whose novel is stolen and published by a white, French writer who had promised to help him. The Black Docker is no doubt a flawed novel, but it engages in far more complex ways with form than most critics allowed (a trend that would mark criticism of his work throughout his career).

Sembène’s epic novel, God’s Bits of Wood (1960), is his most celebrated work. Set across three locations in French West Africa, deploying a host of vivid characters, the novel repurposes the realism of the great French novelist Émile Zola to represent a historical railway strike along the Dakar-Bamako line. God’s Bits of Wood established Sembène as one of the most important literary voices of an Africa emerging from empire — most of the French sub-Saharan colonies gained their independence in the year of its publication — and it has gone on to become a staple of school curricula across the continent.

After more than a decade away from Africa, Sembène returned there in 1960. He had left as a young man in search of adventure and now returned as a politically committed artist who wanted to change the world. Touring the continent to witness the process of decolonization for himself, he realized that his powerful literary representations of ordinary Africans struggling against the twin forces of empire and capitalism could not reach the vast majority of the population who were unable to read European languages. This was when he decided to turn to filmmaking.

Sembène, the Screen Griot

In 1962, Sembène traveled to Moscow to train as a filmmaker at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), under the supervision of Soviet director Mark Donskoï. Upon his return to Senegal, he set about making his first short film, Borom Sarret, a work that borrowed heavily from Italian neorealism to tell a day-in-the-life story of a poor cart driver struggling to make ends meet.

The protagonist’s profession provided the film with its episodic, peripatetic structure. This allowed Sembène to sketch a portrait of the challenges facing a newly independent nation, emerging from a century of colonialism into a capitalist world order still dominated by the former colonial masters.

Despite its limited budget and the difficult technical conditions surrounding the production — it was impossible to capture live sound or even to view nightly rushes after a day’s filming — Borom Sarret was a supremely confident debut film. It showcased Sembène’s skill in creating dramatic tension and forging striking shot compositions that live long in the memory.

As with his first novel, the film also reflected on the role of the African creative artist in the world emerging from empire. In the years that followed, Sembène and his fellow African filmmakers were regularly categorized as “screen griots.” In shorthand, this positioned them as contemporary descendants of traditional African storytellers.

However, midway through Borom Sarret, the cart driver encounters an actual griot, who sings the praises of his family line — despite his current poverty, the cart driver actually comes from a noble lineage — leading him to hand over his hard-won earnings to the praise singer. Traditionally griots were attached to noble families whose stories they committed to memory and on whose patronage they relied.

This scene depicts the modern relationship between griot and patron as debased and commodified. If Borom Sarret announces Sembène as a screen griot, then this involves a break with the past rather than continuity.

Black Girl: A Vision of Neocolonial Alienation

Borom Sarret was financed with embryonic funding from what would eventually become a more systematic cultural cooperation scheme between France and its former colonies. French funding allowed Francophone Africans to develop a body of filmmaking well before their counterparts in Anglophone or Lusophone Africa. Yet the initial obligation (later scrapped) to make films in French often proved a creative straitjacket.

Moreover if you wanted your films to reach a wide audience, the French Ministry for Cooperation was hardly the ideal producer. Far too often, Francophone African films found themselves circulating via diplomatic and educational channels, making it to Western film festivals if they were lucky but rarely gaining general release in Africa or the West. To combat these distribution problems, throughout his career Sembène would personally tour his films around West Africa, organizing screenings and debates with local audiences.

Sembène was one of the few African filmmakers whose work reached cinephile audiences around the world. His breakthrough film was his first feature-length work, Black Girl (1966), which tells the story of Diouana, a young Senegalese woman who works as a nanny for a French expatriate couple in Dakar. At the end of their overseas mission, they decide to take her back to the south of France with them, which for Diouana is the realization of a dream.

As she is driven along the Côte d’Azur, there is an abrupt shift from black-and-white to color images, as she stares out the window in wonder (although these color scenes do not feature in some prints of the film, including the one used to create the current DVD copy). However, while the family lived a life of luxury in Dakar, back home, they live in a small flat. Diouana is not just a childminder, but a cook and cleaner too.

The film constitutes a compelling critique of neocolonial politics, but it is also a troubling study in alienation, as Diouana comes to realize that the Western ideals of consumerist modernity are inaccessible to her. This causes her to despair and ultimately to take her own life.

Rather than offering meticulously observed depictions of Diouana’s lived reality, the film’s emotional and political force resides in a series of bold images. Sembène’s camera lingers on Diouana as she sweeps the floor of the flat while wearing high heels, a stylish polka-dot dress, and striking daisy earrings.

Then when the French father returns her belongings to Dakar, Diouana’s little brother picks up the African mask that had been offered to the family as a gift, becoming a piece of exotic art adorning their nondescript flat. Now the boy holds the mask over his face and stalks the Frenchman as he flees to his car, transforming the mask into a symbol of African resistance.

Mandabi: The Absent Power of Money

Sembène’s next film, Mandabi (The Money Order), his first shot in color, has often been overlooked in assessments of his career, considered to be a slight comedy (although its 2021 rerelease in a newly restored print by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation is prompting a reassessment). Mandabi tells the story of Ibrahima Dieng, played by the peerless Makhourédia Guèye, a mainstay of Senegalese cinema over three decades.

Dieng is a hapless, unemployed, illiterate man with two wives, multiple children, and zero understanding of modern, bureaucratic, capitalist Senegal. When his nephew in Paris sends home a money order, it seems like the answer to all Dieng’s financial problems. However, through a series of tragicomic mishaps, it ends up making them worse.

Essentially the film depicts the struggles of a communal-based society — with its own hierarchies and inequalities — seeking to come to terms with a world governed by money. But it is paradoxically a film from which physical money is largely absent.

The money order that sets the film’s plot in motion is invested with the desperate dreams of people who live their lives hand to mouth, eking out whatever credit they can obtain. Although the urban poor of late 1960s Senegal seek to live by the values and customs into which they were born, the power of money is now in the process of transforming and undermining all they hold dear.

Sembène and Third Cinema

Between 1971 and 1976, Sembène would push his twin exploration of cinematic form and political critique in an increasingly experimental direction. In a trilogy of highly ambitious films, he tackled French colonialism (Emitaï, 1971), neocolonialism in postindependence Senegal (Xala, 1974), and the complex nexus of slavery, colonialism, and Islam in Ceddo (1976). These works would become classics of Third Cinema, the sweet spot where the energy and independence of the French New Wave met the radical politics of Frantz Fanon’s theories of decolonization.

Xala offers a scathing critique of the Senegalese bourgeoisie, cast as a parasitic elite who act as intermediaries for the former colonial powers. They wash their cars with bottles of Evian water and fetishize Western consumer goods. The film’s celebrated opening scene presents independence in Brechtian fashion as a choreographed dance in which the former colonizers are symbolically removed from positions of authority. However, while the latter retreat from the foreground, they remain resolutely present in the background and are quite clearly the true source of authority and power, both economic and military.

The xala of the title refers to the curse of impotence that strikes down a member of this neocolonial elite, El Hadji Abdou Kader Bèye, allowing Sembène to indulge in some viciously bawdy humor at his expense. In an echo of Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, it is the destitute and the outcast of society who punish the sins of the bourgeoisie. Several characters explicitly voice an ideological critique of neocolonialism, but the grotesque and humiliating punishment of El Hadji is primarily driven by a moral anger and desire for revenge.

Imagining Alternatives

Between 1962 and 1976, Sembène directed eight films (also publishing five books), works that may have retained a core of “realism” but that were in fact of an incredible aesthetic diversity. Indeed, this may rank as the single richest period of artistic productivity of any African writer or director in the postcolonial era.

Sembène’s archenemy, Senegal’s poet-president Léopold Sédar Senghor, banned Ceddo, and Sembène would not make another film for over a decade. In the early 1980s, it may have seemed as though his career were petering out. However, in a late burst of creativity, Sembène went on to direct four films between 1988 and 2004.

By and large, these later works saw him return to the realism of his early period. Yet his late masterpiece, Mooladé (2004), a scathing denunciation of female genital mutilation in rural West Africa, demonstrates that his work is rarely content to depict the world as it is. What interests Sembène is the attempt to imagine alternatives to the status quo, to represent potential ways of offering resistance to the powerful.

The film creates a narrative opposition between the forces of change and those of conservative, patriarchal authority: the images of the women’s radios being burned by the men in front of the village mosque are a stark visual representation of the conflict. As in his earlier films, what matters is the representation of fundamental realities, not a closely observed realism that depicts the world as it is but cannot imagine how to change it.

Sembène Today

Sembène died, aged eighty-four, in 2007, two-thirds of the way through making a late trilogy of films, committed right to the end to his filmmaking practice. A very private man, he divulged almost nothing of his personal life in interviews and the few, partial biographies have focused largely on his political and creative development. The documentary film Sembène! (2015) is undoubtedly the best introduction to his life and career, refusing to turn a blind eye to the dark side of Sembène’s character (not least his “theft” of the idea for the film Camp de Thiaroye from two young Senegalese creators).

But what of the legacy of his films? It says much about the ongoing marginalized status of African cinema that the availability of Sembène’s films remains limited to a handful of works. Recent rereleases of Black Girl and Mandabi have been very welcome, but classics such as Xala and Ceddo remain difficult to track down.

Sembène’s legacy as an artist will only endure if audiences — not least in Africa — manage to encounter and engage with his work. In a world of ever-growing inequalities, Sembène’s capacity to imagine alternatives is precisely what we need.