Scabby the Rat Lives, But His Enemies Never Sleep

The labor movement’s iconic inflatable rat has survived a pathetic judicial attempt at extermination. But though Scabby is free, unions remain hamstrung by the oppressive federal prohibition on secondary boycotts encoded in the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act.

A local teamster gets Scabby the Rat ready for a protest in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, 2010. (Juana Arias / the Washington Post via Getty images)

After a years-long crusade within the federal government against the labor movement’s favorite inflatable picket-line prop, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) has granted reprieve to Scabby the Rat.

The campaign to exterminate Scabby, an enormous grotesque balloon villain symbolizing anti-union employers, was a personal project of Peter Robb, who was appointed by Donald Trump to be the board’s general counsel in 2017.

Decades prior, Robb had worked on behalf Ronald Reagan to sue striking air traffic controllers, whose brutal defeat in 1981 is generally considered a turning point in the labor movement, portending its steep decline. After that, he worked for an anti-union law firm called Proskauer Rose.

As NLRB general counsel, Robb took brazen anti-worker stances, such as arguing that Uber workers should be considered contractors rather than employees and consequently stripped of normal employee benefits and protections.

Robb was said to “hate the rat,” and pursued its demise.

He made his move against the iconic rodent after a business brought forward a complaint about a 2018 protest staged by International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE) Local 150, based outside of Chicago. It happened to be the very union local that created Scabby.

IUOE Local 150’s current president is Jim Sweeney, who first came up with the idea for the inflatable rat mascot in the late 1980s. Seeking to publicly shame and pressure employers who hire nonunion contractors, Sweeney decided that he and another union organizer would dress up like heinous rats at protests.

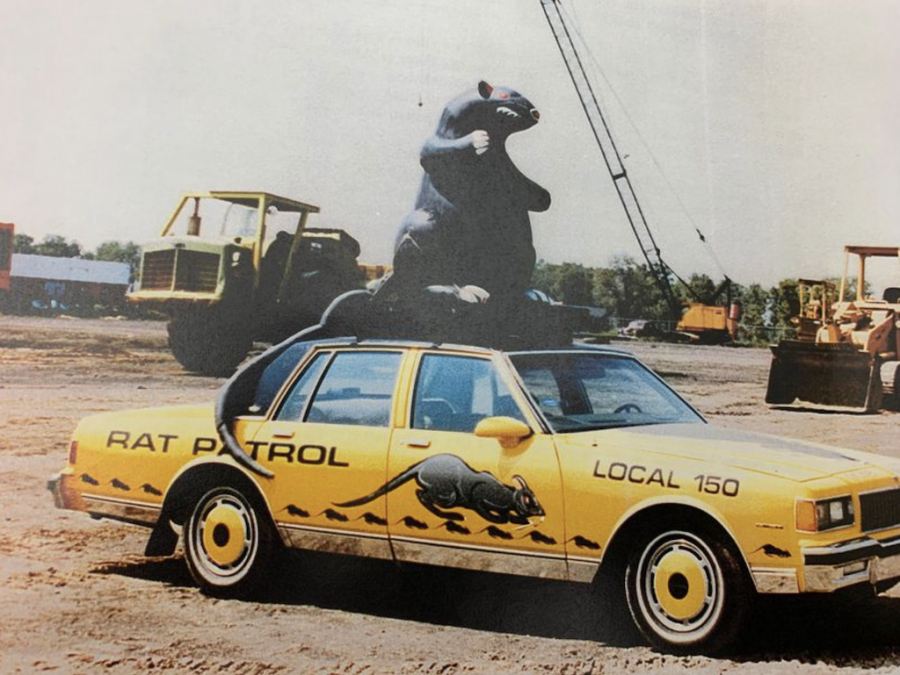

But the costumes proved oppressive to the wearer, and so Sweeney’s solution was a rat figure with nobody inside. At first IUOE’s inflatable rat rode atop a yellow Chevy Impala, emblazoned with the words “Rat Patrol.” Then union organizers noticed an imposing inflatable gorilla outside a car dealership, and decided they needed a freestanding, towering inflatable of their own.

The union held a contest to name the rat. The winner was Scabby, a reference to the creature’s physical repulsiveness as well as to “scabs,” or nonunion hires brought in to replace union workers during a strike. Over the decades, Scabby’s popularity grew. Sweeney says that he realized they’d hit the big time when Scabby appeared in a 2002 episode of The Sopranos.

Thirty years later, IUOE Local 150 was still riding with Scabby. In 2018, the union staged a protest at a RV trade show in Elkhart, Indiana, which grabbed the attention of Scabby’s archnemesis Peter Robb.

The protest targeted a company called Lippert, which was renting equipment from a company called McAllister. The union was embroiled in a labor dispute with McAllister, but not with Lippert. They wanted Lippert to stop doing business with McAllister, as a means of placing pressure on the latter.

IUOE Local 150 arrived at the prominent trade show with Scabby in tow. As usual, he was not just any pedestrian rat but a rat king, a revolting beast with glowing red eyes, fangs, claws, and unsightly sores on his belly. Next to Scabby were two large banners which read, “Shame on Lippert Components, Inc., for Harboring Rat Contractors,” and, “OSHA Found Safety Violations Against MacAllister Machinery, Inc.”

After the embarrassing display, Lippert was successfully persuaded to stop doing business with McAllister. But it also brought the case to the NLRB, arguing that the company should have been protected from such tactics on account of its neutrality.

This, thought Robb, was the perfect opportunity to bring down Scabby. The use of the rat in this instance might have been a violation of the provision against secondary boycotts in the Taft-Harley Act, the notorious 1947 anti-union labor law. In American labor law, union actions against an employer with which the union has a direct conflict are protected, but actions against other parties that do business with that employer are prohibited.

The provision has been interpreted in a variety of ways. In 1949, the NLRB decided that Congress had meant to prohibit anything that might be read as a secondary boycott, which it considered “unmitigated evils and burdensome to commerce.” Since then, the constitutionality of bans on certain types of secondary activity, like generating bad publicity, have been found to contradict the First Amendment right to free speech.

These were the parameters of the disciplinary process through which Robb dragged Scabby starting in 2018. Robb wanted the NLRB to ultimately “find it unlawful to picket, strike or handbill with the rat present,” period. In the meantime, he would settle for disciplining Scabby for his appearance in Elkhart. Unfortunately for Robb, he wasn’t able to even punish much less kill Scabby while he was in office. In January of 2021, he became the first NLRB general counsel to be fired by a president.

The new NLRB had no interest in wasting further energy and public resources on Robb’s crusade, and ruled three to one to dismiss the case. Their decision indicates that there’s little appetite on the current board to use the secondary boycott provision to enforce a prohibition on publicly shaming neutral employers.

But the parts of the secondary boycott provision that can’t be set aside on account of free speech issues — for example, those prohibiting a union from convincing another employer’s workers to engage in a sympathy strike — still remain. And they continue to hamstring unions seeking to pressure employers to compensate and treat workers fairly.

The PRO Act would overturn this provision were it to pass in full. Elements of the PRO Act have made it into the current Senate reconciliation bill, but unfortunately it appears the others, many of them substantive, appear to have been shelved. In the meantime, at least Scabby is free.